Observations from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope have provided a surprising twist in the narrative surrounding what is believed to be the first st

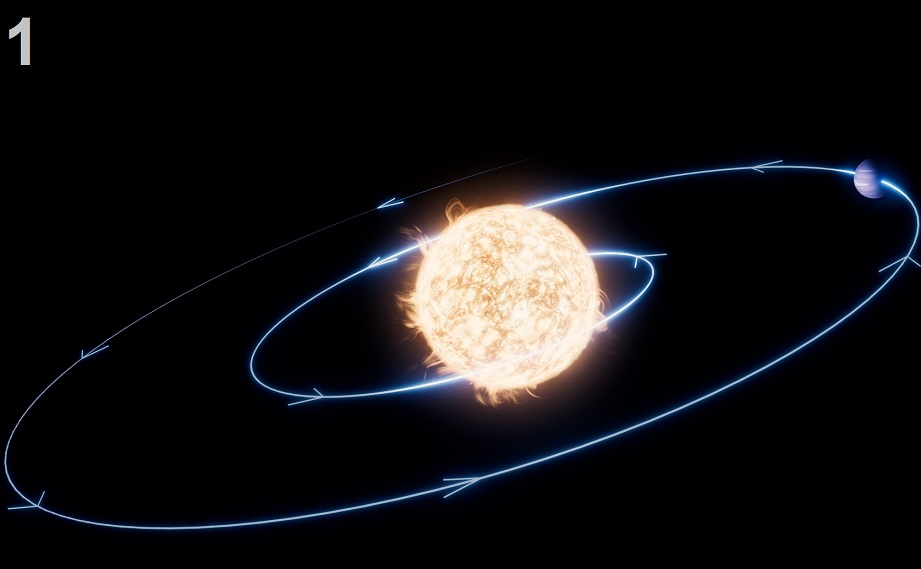

Observations from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope have provided a surprising twist in the narrative surrounding what is believed to be the first star observed in the act of swallowing a planet.

The new findings suggest that the star actually did not swell to envelop a planet as previously hypothesized. Instead, Webb’s observations show the planet’s orbit shrank over time, slowly bringing the planet closer to its demise until it was engulfed in full, reported NASA.

“Because this is such a novel event, we didn’t quite know what to expect when we decided to point this telescope in its direction,” said Ryan Lau, lead author of the new paper and astronomer at NSF NOIRLab (National Science Foundation National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory) in Tucson, Arizona. “With its high-resolution look in the infrared, we are learning valuable insights about the final fates of planetary systems, possibly including our own,” reported NASA.

Two instruments aboard Webb conducted the post-mortem of the scene, Webb’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) and NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph). The researchers were able to come to their conclusion using a two-pronged investigative approach.

The star at the center of this scene is located in the Milky Way galaxy about 12,000 light-years away from Earth, reported NASA.

The brightening event, formally called ZTF SLRN-2020, was originally spotted as a flash of optical light using the Zwicky Transient Facility at Caltech’s Palomar Observatory in San Diego, California. Data from NASA’s NEOWISE (Near-Earth Object Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer) showed the star actually brightened in the infrared a year before the optical light flash, hinting at the presence of dust.

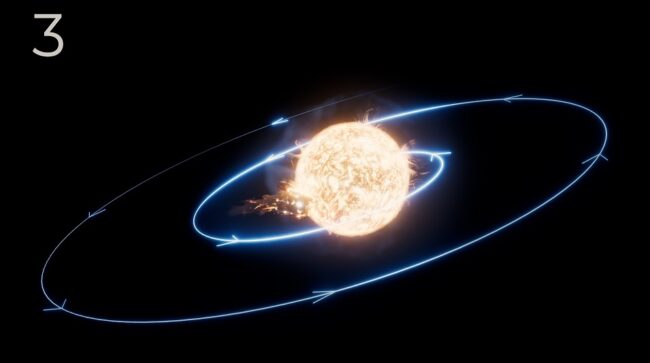

Researchers suggest that, at one point, the planet was about Jupiter-sized, but orbited quite close to the star, even closer than Mercury’s orbit around our Sun. Over millions of years, the planet orbited closer and closer to the star, leading to the catastrophic consequence, reported NASA.

“The planet eventually started to graze the star’s atmosphere. Then it was a runaway process of falling in faster from that moment,” said team member Morgan MacLeod of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “The planet, as it’s falling in, started to sort of smear around the star.”

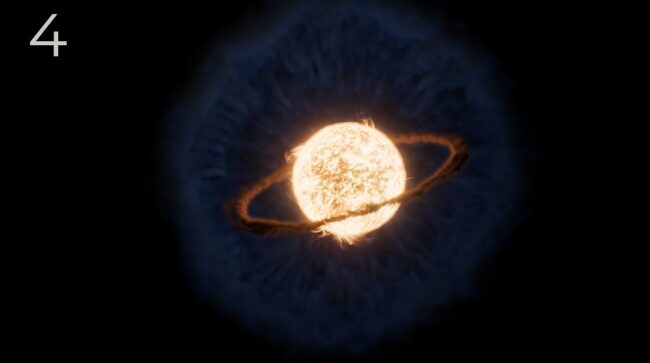

In its final splashdown, the planet would have blasted gas away from the outer layers of the star. As it expanded and cooled off, the heavy elements in this gas condensed into cold dust over the next year, reported NASA.

While the researchers did expect an expanding cloud of cooler dust around the star, a look with the powerful NIRSpec revealed a hot circumstellar disk of molecular gas closer in.

“This is truly the precipice of studying these events. This is the only one we’ve observed in action, and this is the best detection of the aftermath after things have settled back down,” Lau said. “We hope this is just the start of our sample,” reported NASA.

These types of study are reserved for events, like supernova explosions, that are expected to occur, but researchers don’t exactly know when or where. NASA’s space telescopes are part of a growing, international network that stands ready to witness these fleeting changes, to help us understand how the universe works.

Researchers expect to add to their sample and identify future events like this using the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory and NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, which will survey large areas of the sky repeatedly to look for changes over time, as reported by NASA.

All Credit To: webbtelescope.org

COMMENTS