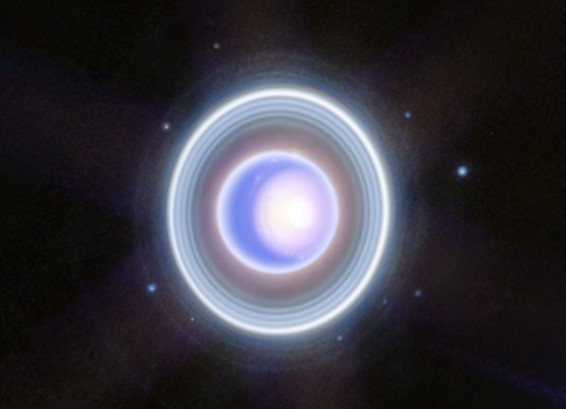

When Voyager 2 flew past Uranus in 1986, the planet appeared to be a nearly featureless, solid blue ball. Now, Webb shows us an infrared view that is

When Voyager 2 flew past Uranus in 1986, the planet appeared to be a nearly featureless, solid blue ball. Now, Webb shows us an infrared view that is much more dynamic and intriguing, reported NASA.

Rings, moons, storms, and a bright, north polar cap grace these new images.

Because Uranus is tipped on its side, the polar cap appears to become more prominent as the planet’s pole points towards the Sun and receives more sunlight, a time called solstice. Uranus reaches its next solstice in 2028, and astronomers will watch for changes in the planet’s atmosphere, reported NASA.

Studying this ice giant can help astronomers understand the formation and meteorology of similarly sized planets around other suns.

The image expands upon a two-color version released earlier this year, adding additional wavelength coverage for a more detailed look.

With its exquisite sensitivity, Webb captured Uranus’ dim inner and outer rings, including the elusive Zeta ring, the extremely faint and diffuse ring closest to the planet. It also imaged many of the planet’s 27 known moons, even seeing some small moons within the rings, reported NASA.

In visible wavelengths as seen by Voyager 2 in the 1980s, Uranus appeared as a placid, solid blue ball. In infrared wavelengths, Webb is revealing a strange and dynamic ice world filled with exciting atmospheric features.

One of the most striking of these is the planet’s seasonal north polar cloud cap. Compared to the Webb image from earlier this year, some details of the cap are easier to see in these newer images. These include the bright, white, inner cap and the dark lane in the bottom of the polar cap, toward the lower latitudes, reported NASA.

Several bright storms can also be seen near and below the southern border of the polar cap.

The polar cap appears to become more prominent when the planet’s pole begins to point toward the Sun, as it approaches solstice and receives more sunlight. Uranus reaches its next solstice in 2028, and astronomers are eager to watch any possible changes in the structure of these features. Webb will help disentangle the seasonal and meteorological effects that influence Uranus’s storms, which is critical to help astronomers understand the planet’s complex atmosphere, reported NASA.

Because Uranus spins on its side at a tilt of about 98 degrees, it has the most extreme seasons in the solar system. For nearly a quarter of each Uranian year, the Sun shines over one pole, plunging the other half of the planet into a dark, 21-year-long winter.

Uranus can also serve as a proxy for studying the nearly 2,000 similarly sized exoplanets that have been discovered in the last few decades. This “exoplanet in our backyard” can help astronomers understand how planets of this size work, what their meteorology is like, and how they formed. This can in turn help us understand our own solar system as a whole by placing it in a larger context, as reported by NASA.

All Credit To: NASA, ESA European Space Agency

and CSA the Canadian Space Agency

COMMENTS