Julia Molins captures in images the people around cleft lip and palate patients, their medical treatment, resilience and folk stories that present a

Julia Molins captures in images the people around cleft lip and palate patients, their medical treatment, resilience and folk stories that present a glimpse of their drama.

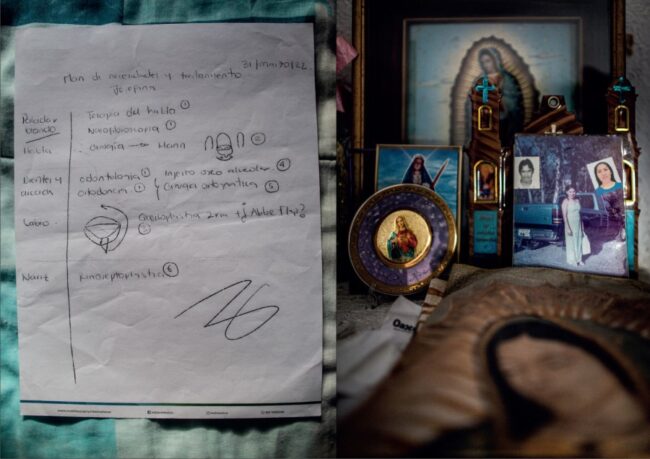

“Upon birth, the moon descended and ate your lip.” Josefina’s grandmother used to tell her this story when Josefina was a child and asked why she was different from other children. It is one of the local stories that were shared to me when I met families affected by cleft lip and palate in Oaxaca, a state in southern Mexico, reports Julia Molins for Elsevier Ltd. and The Lancet.

I started working as a clinical and documentary photographer for the non-governmental organisation (NGO) MSI-Mobile Surgery International in 2021. The NGO runs a mobile hospital where a team including surgeons, psychologists, dentists, and therapists, among others, provides free comprehensive care to people born with cleft lip and palate.

The hospital is located in Oaxaca, and many of the patients are from low-income, rural communities. Living in poverty can delay access to care for cleft lip and palate and affect treatment outcomes. Additionally, social stigma about the condition has implications in relation to education, employment, and integration in the wider community, reports The Lancet.

During the process of taking portraits of patients in Oaxaca, I encountered children, teenagers, and adults and a bond was formed with some individuals. They began to tell me about their daily lives and what they had been through.

Josefina explained to me how when she was just 4 years old, her father died near the US–Mexico border while he was trying to cross to send money and pay for her surgeries, reports The Lancet.

Irene buried her first child because no one explained how to feed a baby with cleft lip and palate. Felipe cried as he recalled how he was insulted in school because of his condition.

Documenting the lives of these individuals for 3 years has highlighted the importance of access to comprehensive, safe, and free treatment. But beyond the medical aspect, these photographs capture resilient people who, despite their socioeconomic context, experiences of stigma, or the imprint of local superstitions, continue to live every day so that they are not seen as victims, but as survivors enjoying life despite the social injustices they face, reports The Lancet.

I thank Dr Nicolas Sierra, Dr Diana Bohórquez, and MSI-Mobile Surgery International, for their work and resilience in the face of adversity, their care for families, and the trust during the years I have taken photographs for this project. This project was supported non-financially by MSI-Mobile Surgery International, as reported by The Lancet.

All Credit To: The Lancet / Elsevier Ltd. / Text-Photos: Julia Molins

COMMENTS