A team led by researchers at the University of Montreal has found evidence that two exoplanets orbiting a red dwarf star are "water worlds," where wa

A team led by researchers at the University of Montreal has found evidence that two exoplanets orbiting a red dwarf star are “water worlds,” where water makes up a large fraction of the entire planet. These worlds, located in a planetary system 218 light-years away in the constellation Lyra, are unlike any planet found in our solar system, reported NASA.

The team, led by Caroline Piaulet of the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets at the University of Montreal, published a detailed study of this planetary system, known as Kepler-138, in the journal Nature Astronomy.

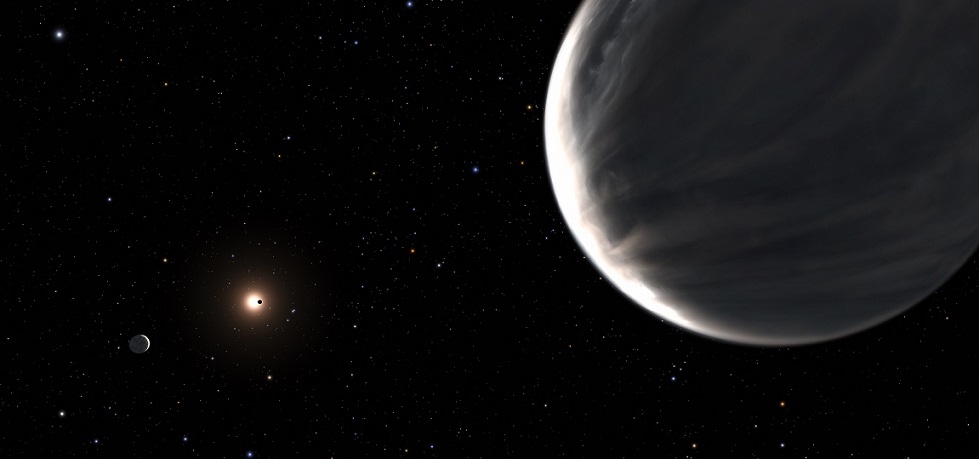

Piaulet and colleagues observed exoplanets Kepler-138 c and Kepler-138 d with NASA’s Hubble and the retired Spitzer space telescopes and discovered that the planets could be composed largely of water. These two planets and a smaller planetary companion closer to the star, Kepler-138 b, had been discovered previously by NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope. The new study found evidence for a fourth planet, too.

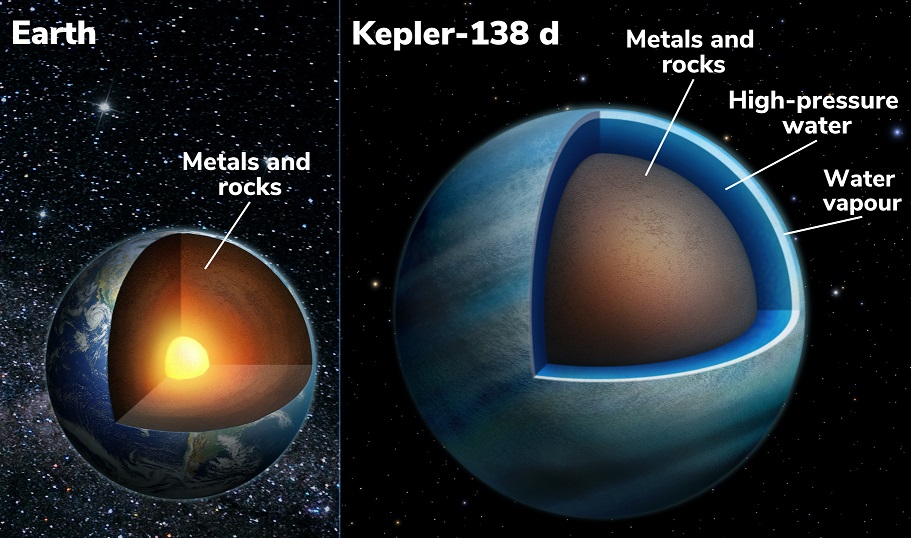

Water wasn’t directly detected at Kepler-138 c and d, but by comparing the sizes and masses of the planets to models, astronomers conclude that a significant fraction of their volume –up to half of it– should be made of materials that are lighter than rock but heavier than hydrogen or helium (which constitute the bulk of gas giant planets like Jupiter). The most common of these candidate materials is water.

“We previously thought that planets that were a bit larger than Earth were big balls of metal and rock, like scaled-up versions of Earth, and that’s why we called them super-Earths,” explained Björn Benneke, study co-author and professor of astrophysics at the University of Montreal. “However, we have now shown that these two planets, Kepler-138 c and d, are quite different in nature and that a big fraction of their entire volume is likely composed of water. It is the best evidence yet for water worlds, a type of planet that was theorized by astronomers to exist for a long time.”

An artist’s illustration shows a cross-section of the Earth (left) and the exoplanet Kepler-138 d (right). Like the Earth, this exoplanet has an interior composed of metals and rocks (brown portion), but Kepler-138 d also has a thick layer of high-pressure water in various forms: supercritical and potentially liquid water deep inside the planet and an extended water vapor envelope (shades of blue) above it. These water layers make up more than 50% of its volume, or a depth of about 1,243 miles (2,000 kilometers). The Earth, in comparison, has a negligible fraction of liquid water with an average ocean depth of less than 2.5 miles (4 kilometers).

With volumes more than three times that of Earth and masses twice as big, planets c and d have much lower densities than Earth. This is surprising because most of the planets just slightly bigger than Earth that have been studied in detail so far all seemed to be rocky worlds like ours. The closest comparison, say researchers, would be some of the icy moons in the outer solar system that are also largely composed of water surrounding a rocky core, reported NASA.

All credit to: NASA.gov